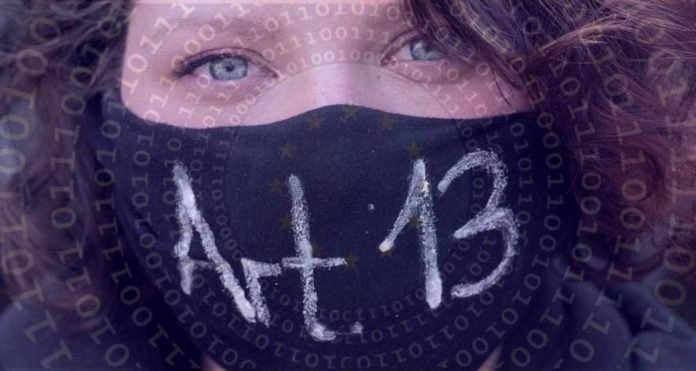

The European Parliament has today approved the Copyright in the Digital Single Market Directive including the controversial Article 11 and Article 13 (which has now been renamed Article 17) by 348 to 274 votes against the advice of academics, technologists, and UN human rights experts.

These new laws which require force platforms such as YouTube and Facebook to filter or remove copyrighted material from their websites will come into effect from 2021.

Julia Reda, a German MEP and long-time vocal opponent of the move, described the decision as a ‘dark day for internet freedom’. Germany has been at the head of the anti-reform movement, which has been led by Reda, the 32 year-old Pirate Party MEP at the head of the campaign for the past three years since the proposals were first introduced. The MEP warned that Article 13 would require platforms to install expensive content filters that would automatically and often erroneously delete content from the web.

https://juliareda.eu/2019/02/eu-copyright-final-text/

After saying the vote marked ‘a dark day for internet freedom’, Reda decried that MEPs refused, albeit narrowly, to modify the text before the final vote.

Google and Facebook have both denounced the European Union’s controversial new copyright reforms, saying they will hurt the sector’s creative and digital economies as well as the freedom of users to re-post news content on social media sites. Its opponents claim they could restrict online freedom of speech, and force websites to install filters that effectively act as a brake to prevent them posting news content.

Article 11, dubbed the link tax, will require news aggregators (websites that help users find all popular news sites articles by gathering them in one place) and others to pay a charge when they link to certain articles on the web. It is thought that these laws, which take the form of licensing agreements, will hand greater powers to news publishers and record companies who will now be able to enforce compensation from internet providers and social media sites.

With it now highly likely that the Copyright in the Digital Single Market Directive will become EU law; any rejection would require at least one member state to vote against the Directive when the 27 Heads of national governments that make up the European Council meet at the end of this month.

If it goes through as expected, member states will have until 2021 to ratify the Copyright Directive into their own laws. Germany, Austria, Portugal and Poland have recently seen major demonstrations over the new law which has further intensified public opposition and both governments are likely to proceed cautiously with this schedule.

German and Polish activists are already re-doubling their efforts to shift their government’s key votes in their respective Parliaments. Despite an online petition which has gathered five million signatures, the campaign has largely failed to attract the attention of the European press outside the two countries.

The Electric Frontier Foundation, an international non-profit digital rights group based in San Francisco, California, which has also opposed the legislation states:

‘We can expect media and rights holders to lobby for the most draconian possible national laws, then promptly march to the courts to extract fines whenever anyone online wanders over its fuzzy lines.’

‘The Directive is written so that any owner of copyrighted material can demand satisfaction from an Internet service, and we’ve already seen that the rights holders are by no means united on what Big Tech should be doing.’

However, the EFF added that ambiguities in the Directive also provide opportunities for opponents to rein in the most severe aspects of the legislation if they can maintain their campaign of opposition to the legislation.

Raffaella De Santis, associate at law firm Harbottle & Lewis has also commented about the legislation:

‘Artists and creators will hail the passing of the Directive as a real victory for their right to be fairly paid for their creations. However the effect of the text of the Directive as passed could at the same time have very concerning and unintended consequences for vast swathes of online services, not simply those operating in music or news. This outcome is unpopular with digital services and importantly, many European voters.’

‘The key focus now will be on how the Directive is implemented across the EU over the next two years, and care will need to be taken to ensure that smaller services are not disproportionately disadvantaged by measures which are in reality designed to curtail the formerly unchecked power of the tech giants.’

EU member states have two years to implement the law, although it is not clear what it would mean for the UK in the face of its departure from the European Union.

‘Whether the UK leaves Europe with or without a deal, it’s hard to see that it would not follow Europe’s lead on this, whatever the respective outcomes of the EU vote tomorrow and Brexit,’ De Santis added.

Agence France-Presse (AFP) and other publishing corporations have lobbied hard for the reform with EU Commissioners, holding the view that it as an urgent remedy to safeguard quality journalism and the plummeting earnings of traditional media companies. However, its opponents argue that Article 11 dubbed the “link tax” will stifle discourse on the internet and pay only big media companies, with no real benefits for journalists or news gatherers.

The legislation is also strongly opposed by Silicon Valley and European technology start-up companies which receive profits from the advertising generated on content it hosts, and also by supporters of a free internet who fear it will result in unprecedented restrictions to web freedom.

Catherine Stihler, chief executive of Open Knowledge International, said: ‘This vote is a massive blow for every internet user in Europe.

‘MEPs have rejected pleas from millions of EU citizens to save the internet, and chose instead to restrict freedom of speech and expression online.’We now risk the creation of a more closed society at the very time we should be using digital advances to build a more open world where knowledge creates power for the many, not the few.’

‘But while this result is deeply disappointing, the forthcoming European elections provide an opportunity for candidates to stand on a platform to seek a fresh mandate to reject this censorship.’

It is likely that the first implementation of the Directive will come from those member states which have most enthusiastically supported its passage. French politicians have consistently advocated for the most controversial parts of the Directive, and the Macron administration may push forward strongly on the legislation in an attempt to placate the country’s media establishment.

In Poland, politicians have been besieged by an angry public wanting them to vote down the Directive, while simultaneously facing strong denunciations from national and local newspaper owners warning that they would “not forget” any politician who voted against the legislation.

The Christian Democratic Union, whose own Axel Voss has strongly supported the Directive, put out a policy proposal that suggested it could implement Article 13 without filters, but with a blanket-licensing regime. Legal experts have already said that these licenses won’t comply with the legislation’s stringent copyright requirements.

One key contradiction at the heart of the Directive will have to be resolved very soon. Article 13 is supposed to be compatible with the older E-Commerce Directive, which explicitly forbids any requirement to proactively monitor for IP enforcement (a provision that was upheld and strengthened by the European Court of Justice in 2011). Any law mandating filters could be challenged to settle this inconsistency in the European Courts, leading to drawn-out and intensive legal battles.

Europe’s Internet users can’t depend on the tech companies to fight this. The battle will have to continue, as it has done in these last few weeks, with millions of everyday users uniting online and on the streets to demand their right to be free of censorship, and free to communicate without algorithmic censors or arbitrary licensing requirements.

If member states implement the new directive, it is highly probable that human rights advocates and campaign groups will bring a challenge to the European Court of Justice, in an important test case to see how they evaluate fundamental rights versus copyright laws that mainly benefit media conglomerates.

It may well be that activists and campaigners will need to organize and support independent European digital rights groups (https://edri.org/) willing to legally challenge the Directive. Ahead of the next European Parliament elections, this vote comes as another important reminder of the impact that EU law-making can have on the rights of users online.

In the 17th century as the first English newspapers appeared Milton argued that having to pass through censorship before reaching the public has a vast impact on what is said, and even what is thought. Having a gatekeeper makes it easier for the rich and powerful—those with connections in high places—to speak and to silence others.

An internet where the creator of a new web space for conversation is required to pay huge fees to media giants before even launching is no different from the world Milton feared, where the free circulation of information remains the privilege of publishing corporations and media moguls. The internet is a legacy that can decisively shape our future for the better within a broadly defined ‘common good. Let’s make sure it remains a free, innovative, and inclusive voice for all.

This is a "Pay as You Feel" website Please help keep us Ad Free.

You can have access to all of our online work for free. However if you want to support what we do, you could make a small donation to help us keep writing. The choice is entirely yours.

You must be logged in to post a comment.